Dean Nelson, Director, Museum of CT History

First published in The CONNector, Volume 20, No 1 – Winter 2018

Scholars of early American technology and innovation praise three New England gun makers for mastery of identical parts interchangeability; laurels and accolades go to: Eli Whitney (New Haven, Connecticut) for Model 1798 contract muskets, Simeon North (Berlin and Middletown, Connecticut) for 1812-era contract pistols and John H. Hall (Portland, Maine and Harpers Ferry, Virginia) for Model 1819 Hall patent rifles. Interchangeability fostered manufacturing efficiencies and ease of repair to broken guns, especially the intricacies of the lock mechanism. For obvious reasons, the U. S. War Department had the keenest interests in ensuring firearms parts interchangeability, initially in its own National Armories at Springfield, Massachusetts and Harpers Ferry, Virginia and subsequently with private arms contractors gaining government orders for military firearms. Firearms authority Peter A. Schmidt, in his indispensible U. S. Military Flintlock Muskets, the Later Years (2007) quotes an 1819 Ordnance Department report “On the subject of uniformity of arms….it will be necessary to have a set of original patterns and gauges of each and every part…sealed and kept in the Ordnance Department at Washington, and to cause those [gauges] of the superintendent of each factory to be sent occasionally to that office, to be compared with them and fitted anew, if required.”

Few gauge sets (or even stand-out individual keepsake gauges) for American flint and percussion firearms have survived discard and loss, once they were rendered obsolete by newer models of guns. The earliest is a partial set for Harper’s Ferry Model 1816 Muskets, dated 1826, sold at auction a decade or so ago. Schmidt’s book features a remarkable complete set for the 1816 musket stamped “USMl/1832/Ay.” Two sets exist for the U.S. Model 1841 Rifle, with guns produced at Harper Ferry Armory and by 5 private contractors, including Eli Whitney, Jr., (New Haven, CT). The Smithsonian Institution’s set was installed in a long-running exhibit Engines of Change and graces the accompanying book of the same name. Harper’s Ferry National Historical Park’s set is regularly an educational display at the Maryland Antique Arms Collectors’ annual Baltimore Gun Show. There is a partial 1841 gauge set in a private collection. So, military gauge sets, as crucially important as they were at the time, are today very few and far between.

With this backdrop, the Museum was electrified to be the successful bidder on one complete gauge set and three incomplete sets, to inspect the U. S. Model 1842 Pistol, which was manufactured exclusively under government contracts in Middletown, CT, first by Henry Aston, then Henry Aston & Company, and third by his business partner, Ira N. Johnson. Our study of these has only just begun; we have been in contact with a researcher working towards a publication about single-shot American military pistols who has conducted exhaustive research in the National Archives. He is planning a visit and we warmly welcome his alliance.

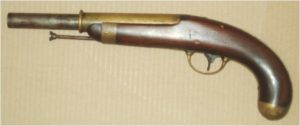

Figure 1: The U.S. Model 1836 Pistol (top) was superseded by the U.S. Model 1842 Pistol, below. The salient differences included substitution of the new War Department-wide percussion ignition system, far more reliable than the old flint and steel ignition, and brass, rather than iron, hardware for the walnut stock. Generally, both the ’36s and ’42s were issued in pairs to dragoons (mounted troops) and carried in two connected heavy leather flapped holsters slung in front of the saddle. The loading ramrod, for seating the round bullet on the main powder charge, was held in a swivel to prevent its loss.

The internet phenomena YouTube hosts videos of these military pistols being fired; be aware that dangerous loading practices, especially a hand in front of loaded barrels, are alarmingly common.

Ab ove: U.S. Model 1836 Pistol by R. Johnson, MCH accession #TG1324: Robert Johnson contracted for and delivered some 18,000 flintlock, single-shot, .54 caliber (54/100ths of an inch) pistol firing a round lead ball. His pistol works were in the Pameacha Factories complex in Middletown, CT, sited on the Pameacha River at the South Main Street bridge, the south part of town.

ove: U.S. Model 1836 Pistol by R. Johnson, MCH accession #TG1324: Robert Johnson contracted for and delivered some 18,000 flintlock, single-shot, .54 caliber (54/100ths of an inch) pistol firing a round lead ball. His pistol works were in the Pameacha Factories complex in Middletown, CT, sited on the Pameacha River at the South Main Street bridge, the south part of town.

Below: Model 1842 Pistol by H. Aston, MCH accession #2017.505.2; Henry Aston produced 24,000 for his first contract (1846-51), and an additional 6,000 as H. Aston & Co. (1851-52). The firm sold its factory and all its assets to business partner Ira N. Johnson (distinguished from flintlock pistol maker Robert Johnson, of uncertain kinship) in 1852. I. N. Johnson, awarded a third and final contract, delivered 10,000 from 1853-55. Most pistols in the three contracts went to the U. S. War Department, though perhaps a limited number with imperfections that failed government inspection were sold commercially or to state militias.

Figure 2: Model 1836 Pistol lock marking detail: “US/R. JOHNSON, MIDDn CONN/1842.” The black powder priming charge, poured into the brass pan, ignited (usually) when the piece of flint held in the hammer (i.e. cock) struck white hot sparks off the hardened steel of the spring-tensioned pan cover (i.e. frizzen or battery). The mini-explosion flashed through the touch hole to the main charge in the barrel. (Refer to figure 1)

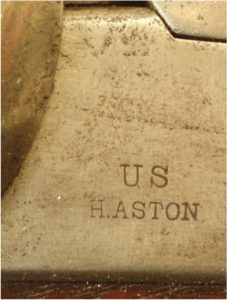

Figure 3: Model 1842: Pistol lock marking detail: “US/H. ASTON.” Percussion ignition employed a small thin cup of brass holding a dab of mercury fulminate, which exploded when struck; hence “percussion.” The cap was set on the cone at the breech and the flame communicated down through the seating bolster to the main charge. The percussion system worked very well even in downpours. (Refer to figure 1)

Figure 4: Aston Model 1842 lock marking detail: “MIDDtn/CONN/1846,” the first year of Aston’s deliveries to the Ordnance Department.

Figure 5: Gauge Set “C” MCH accession #2017.504.1 et al: complete complement of 47 gauges; the beam scale and heavy bronze weight “Apparatus for testing lock springs.”

Figure 6: The gauges with most obvious purpose include #26: “Receiving gauge for lock,” and #8: “Receiving gauge for barrel, with pin for cone seat.” Each part would have undergone gauging before assembly and near-final testing in these more complex fixtures. Earlier collector(s) possessing the gauge sets added four ’42 pistols (three H. Astons and one I.N. Johnson) to disassemble and match-up parts with associated gauges to illustrate their function.

Figure 7: Working shop gauges, unmarked, likely made by Aston/Johnson’s highly skilled gunsmiths/pattern makers, for testing of parts under production to avoid unnecessary wear of the Springfield Armory-made master gauge set provided to them. They are much less finely finished than the Springfield gauges. Interchangeability requires precision tolerances of .002 inch (two-thousandths of an inch).

Figure 7: Working shop gauges, unmarked, likely made by Aston/Johnson’s highly skilled gunsmiths/pattern makers, for testing of parts under production to avoid unnecessary wear of the Springfield Armory-made master gauge set provided to them. They are much less finely finished than the Springfield gauges. Interchangeability requires precision tolerances of .002 inch (two-thousandths of an inch).

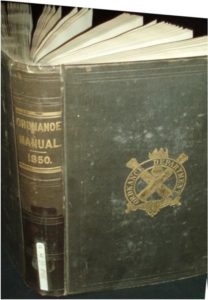

Figure 8: The Ordnance Manual for the Use of Officers of the United State Army, 1850 owned by John Sedgwick, Bvt. Major, U. S. A. Fort McHenry Baltimore April 13th 1850″;

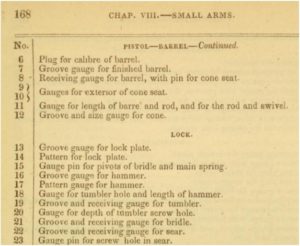

Figure 9: Numbered nomenclature index of the Model 1842 pistol gauges from the 1850 Ordnance Manual.

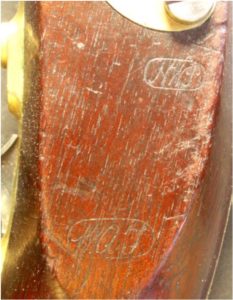

Figure 10: US Ordnance Department Inspector Stamps;”WAT ” for Captain William A. Thornton, chief inspector of contract arms;”NWP” for Nahum W. Patch, civilian inspector of contract arms. These were hand stamped on the stock flat opposite the lock and warranted that the completed arm fully met all contract requirements. Thornton and Patch, at the factory, applied these before crating pistols for shipment.

Figure 11: Johnson Model 1836 Pistol internal lock parts: The workman of this lock deeply struck a “V” on visible surfaces of most parts…lock plate, brass pan, tumbler, bridle, sear and screws…to verify that this group of components had been properly hand fitted to one another. This marking was done while the parts were “soft,” i.e., still workable by milling cutters and files and before they underwent special heat treatment to harden the pieces. After hardening, a file glances off; only abrasive stones can now remove metal. The process reduced prospects of wear and deformation and imparted a brilliant fire-blue to the surfaces. Hardening was tricky to do, given the variables of metal alloy, furnace temperature, and heating time. The internals sometimes were overly brittle and thus susceptible to breakage, underscoring the decided virtue of interchangeable parts in manufacturing and repair. It is a coincidence if parts from one Johnson 1836 pistol lock happen to fit in a second one.

Figure 11: Johnson Model 1836 Pistol internal lock parts: The workman of this lock deeply struck a “V” on visible surfaces of most parts…lock plate, brass pan, tumbler, bridle, sear and screws…to verify that this group of components had been properly hand fitted to one another. This marking was done while the parts were “soft,” i.e., still workable by milling cutters and files and before they underwent special heat treatment to harden the pieces. After hardening, a file glances off; only abrasive stones can now remove metal. The process reduced prospects of wear and deformation and imparted a brilliant fire-blue to the surfaces. Hardening was tricky to do, given the variables of metal alloy, furnace temperature, and heating time. The internals sometimes were overly brittle and thus susceptible to breakage, underscoring the decided virtue of interchangeable parts in manufacturing and repair. It is a coincidence if parts from one Johnson 1836 pistol lock happen to fit in a second one.

Figure 12: Aston Model 1842 Pistol internal parts. In stark contrast to the “V” marks on the non-interchangeable Johnson flint lock, the Aston internals are devoid of assembler marks. The gauging system guaranteed that each and every part that passed gauge would fully, freely, and decidedly fit mating parts that had also passed gauge. Like the 1836 parts, they were soft during the metal-removing phases of their making and then completed by hardening. The springs of the ’36s and ’42s were made of “spring steel” that underwent a different heat tempering process and were polished bright.

Figure 13: Broken U.S. Military Musket Lock Parts, 1817-1865: Hardened internal lock parts were prone to fracture. The Ordnance Manual, 1850, featured a list titled “Spare parts required for the repair of 1000 Percussion Rifles, Musketoons, and Pistols, during one year, in the field.” The Manual noted that for non-interchangeable guns “The spare parts furnished from the armories are in general filed and finished, except hardening and tempering.” The fully interchangeable parts of the Aston & Johnson Model 1842 pistols were issued pre-fitted and hardened and effortlessly replaced the broken part.

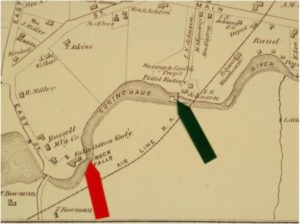

Figure 14: Map detail of Rockfalls, Conn.: The green arrow locates the Aston & Johnson pistol factory. Local historian (and neighbor!) Thomas Atkins in 1883 wrote “This building was built of brick with a stone basement, 80 feet long by 30 feet wide, and two stories high above the basement.” Here it is titled Savage and Smith Pistol Factory. It burned in 1879, five years after this map. Inventor Otis Smith, who did “quite an extensive business there” before the conflagration, bought the property and in 1881 “erected thereon a three-story brick building, 100 feet long by 30 feet wide.” Smith made commercial rim-fire metallic cartridge pocket pistols. That second factory survives and underwent extensive renovation as a private residence not long ago. The red arrow designates Wadsworth Falls, part of the state park of the same name. The factory buildings there are gone; the site is now the natural attraction’s parking lot. The river was variously known as the Coginchaug, the Little River, and the West River in the 19th century, a source of research befuddlement until that is understood. The map does not hint at the area’s actual topography of steep banks, today moderately wooded. From County Atlas of Middlesex, Connecticut, F. W. Beers, 1874.

Figure 14: Map detail of Rockfalls, Conn.: The green arrow locates the Aston & Johnson pistol factory. Local historian (and neighbor!) Thomas Atkins in 1883 wrote “This building was built of brick with a stone basement, 80 feet long by 30 feet wide, and two stories high above the basement.” Here it is titled Savage and Smith Pistol Factory. It burned in 1879, five years after this map. Inventor Otis Smith, who did “quite an extensive business there” before the conflagration, bought the property and in 1881 “erected thereon a three-story brick building, 100 feet long by 30 feet wide.” Smith made commercial rim-fire metallic cartridge pocket pistols. That second factory survives and underwent extensive renovation as a private residence not long ago. The red arrow designates Wadsworth Falls, part of the state park of the same name. The factory buildings there are gone; the site is now the natural attraction’s parking lot. The river was variously known as the Coginchaug, the Little River, and the West River in the 19th century, a source of research befuddlement until that is understood. The map does not hint at the area’s actual topography of steep banks, today moderately wooded. From County Atlas of Middlesex, Connecticut, F. W. Beers, 1874.

Figure 15: Toy “Pop Gun,” circa 1850s. MCH accession #2017.490: Using Model 1842 production components…a walnut stock blank, brass butt cap, back strap and trigger guard, and an iron ram rod…a Mr. “Ashton” (not Aston), stamped his last name atop the brass tube which housed a coil spring and air chamber for this parlor gun. The iron forepart of the barrel was first loaded, using the ram rod to push a 1/2″ diameter cork ball to the bottom. The iron tube was then pulled forward, and held forward by the trigger mechanism. Under stretched-tension by the coil spring, the iron barrel snapped backward by the pull of the trigger. The air in the brass chamber compressed through the iron barrel and propelled the cork ball towards its target. A Peter Ashton was Henry Aston’s main gunsmith and likely this is his creation. In a remarkably humorous touch, the script initials “WAT”-in-an-oval is struck in the left side of the stock near the breech, as on the full-blown government ’42s. The stamp is that of William A. Thornton, U. S. inspector of contract arms, who seemingly was amenable to light-hearted vignettes; (or perhaps his stamp got applied by a prankster?)