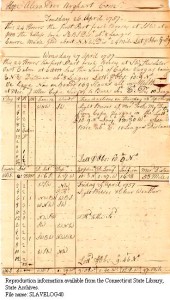

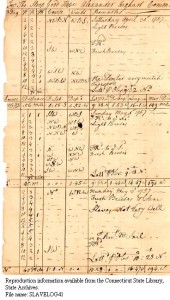

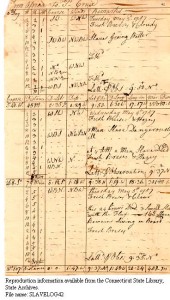

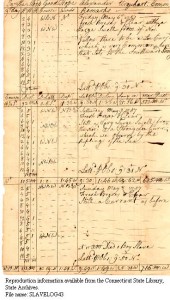

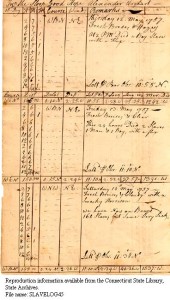

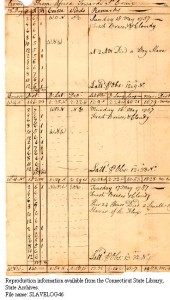

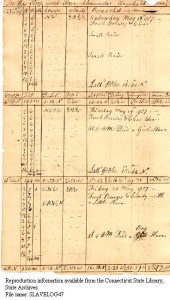

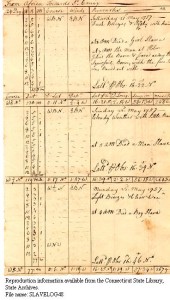

Log Book of Slave Traders between New London and Africa, 1757-8

Introduction

The following nine pages come from the manuscript logbook of one man, Samuel Gould, a Connecticut native who was a first mate or supercargo aboard three slave ships in 1757-58. The first ship, the Africa, sailed from New London to the current West African nation of Sierra Leone, up the Sierra Leone River and anchored at Bunce Island, owned by a British slave trading company. There slavers would purchase Africans kidnapped from the interior of Africa by blacks and would begin the trip west back to the Caribbean where slaves were in great demand for work on rice and sugar plantations. Though Gould sailed to Bunce Island on the Africa, he returned on the sloop Good Hope. The pages of the log accessible here provide a daily account of weather, daily activities and an epidemic of amoebic dysentery that killed African children and adults. For more information about the logs, Bunce Island, the slave trade, and amoebic dysentery, see Anne Farrow, “The Forgotten Story of Connecticut’s Slave Ships,” especially “Part II, Sam Gould and the Isle of Loss,” published in Northeast, Sunday, April 3, 2005, Hartford Courant at http://www.courant.com.The complete logbook is available to researchers in the State Archives of the State Library.

Click on the images below to see a full page of the log.

|

No page 44 |

|

|

Provenance

On September 30, 1920, Cynthia E. Lamm wrote from Southern Pines, North Carolina to Connecticut State Librarian George Godard in Hartford informing him that “among my husband’s antique books,” she had two manuscripts that might interest him: the account book of “supplies and issues of the Continental Frigate `Trumbull’ 1776-1777;” and the Log Book of “three different slavers from New London to Africa and back, 1757-1758.” Lamm did not say how or when her husband acquired these and many more printed books and pamphlets. However, she needed money and wrote Godard that the Librarian of Congress had “made me an offer for them which seemed too small to me.” She knew something about sales for she wisely did not reveal the amount to Godard. In order to increase his interest, she wrote, “I thought as they [the slave ships and the “Trumbull”] sailed from Conn. they would be more valuable to your state.” Godard was interested and on October 6 suggested that she send the manuscripts “by registered mail on approval, with a statement of your price for the same.”

Six days later, Lamm wrote that she had sent the log books to a “book expert” in Philadelphia “to ascertain about their value.” She assured Godard that she would instruct the dealer to “forward them to you.” On October 18, the State Librarian wrote requesting that Lamm “give me an idea of how much you feel you should receive for these volumes.” The State Library could not afford to “pay elaborate prices for records of this kind, although they are interesting.” Most of the historical records in the State Library, he emphasized, “have been donated” by persons whose chief interest was to increase their “safety and accessibility.” He sent Lamm a recent annual report that listed donations.

On October 30, Lamm thanked Godard for the report but disclosed that her “finances will not allow me to have the name of her late husband among the many donors of your valuable library.” The dealer in Philadelphia had estimated the manuscripts to be worth between forty to sixty dollars. If Godard found that he could not afford them, Lamm asked him to forward them to the Library of Congress that had made her an offer. Godard did not waste time. He had received the logbooks and on November 2 sent her a letter of acceptance and check for forty dollars.

On November 4, Lamm wrote that her husband and she had driven through Hartford in 1919. In fact, the two had traveled 5,000 miles “without an accident.” “In March last,” she continued, “he was injured by his car colliding with another crushing him between them.” In those days, in order to start automobiles, drivers had to crank the engine while standing in front of the car. For safety’s sake, manufacturers warned drivers not to start the engine with gears engaged. Unfortunately her husband started the car “with gears in,” and it lurched forward, pinning him between his car and another vehicle. She ended her story of the tragedy stating that “he lived thirty six hours.”

Then she revealed how much the logbooks meant to her husband:

“Please pardon this. I feel badly to sell his books yet

I know that he would think it best under the circumstances.

I have seen him reading these Logbooks many times and it

all comes up so vividly before me.”

Obviously it was difficult for her to part with them.

On November 8th Godard wrote one last time expressing his condolences and sympathy. In previous letters, he had invited her to visit the Library, and he repeated the invitation. We do not know whether Cynthia Lamm ever returned to Hartford. Her husband’s logbooks, however, remain at the State Library and have been available to researchers since the 1920’s.

Compiled by Mark Jones, State Archives, 2005.