Dean Nelson, Director Museum of Connecticut History

First published in The CONNector Magazine Volume 19, No. 4 Fall 2017

Shoulder Arms

Top: U.S. Model 1819 Hall Rifle, Simeon North Contract of 1831, dated 1831; (Accession # 2017.369; purchase)

Below: U.S. Model 1843 Hall/North Carbine,dated 1848

The year 2017 has been particularly benevolent to the Museum’s collections development program, providing closely-timed opportunities to acquire several interrelated early military rifles that embody key “firsts” in the evolution of precision metalworking production. Massachusetts Institute of Technology scholar Merritt Roe Smith in the 1970s identified the historic and technological significances of John Hall’s U. S. Model 1819 Flintlock Breech-loading Rifle — produced at the federal government’s Harpers Ferry, Virginia, Armory — and exacting copies made by Connecticut private arms contractor Simeon North, 308 miles away. ”

…components of the rifles made by North not only exchanged well with each other ‘but equally well with those’ under [Hall’s] immediate supervision at Harper’s Ferry. For the first time fully interchangeable weapons were being made at two widely separated arms factories…No two individuals played a more important role in this development or as machine-tool innovators in general during the early nineteenth century than did North and Hall.” The Hall 1819 breech loader was made to arm Regular Army rifle units and infantry companies protecting the left and right flanks of linear regimental battle formations. Hall made some 20,000 between 1823 and 1829. Rank and file infantry in the Hall rifle era carried traditional flintlock smooth bore muzzle-loaders, of the latest pattern, U.S. Model 1816 Muskets. The Halls could be loaded and fired three times more rapidly than the muzzle loaders, with this added advantage:

The ammunition consisted of .52 caliber (52/100ths of an inch) round lead ball and measured, granulated black powder, either wrapped together in a paper roll, or with powder dispensed from a metal flask with a spring activated nozzle. With the flint hammer at half cock/safety, priming powder was trickled into the pan and the sparking frizzen snapped closed. The main powder charge got poured into the round chamber (slightly tapered) bored into the face of the block and the ball friction fitted in by a finger!? An ignition mishap at this stage could fire the gun, with predictable injury to the marksman. After loading, the ball might dislodge within the closed breech block, loosing powder into the nooks and crannies of the stock inletting. This spillage, unnoticed, could, and did, blow out the thin stock cheeks when the gun was fired. Black powder fouling (water soluble but plaster-hard) on the breech block face routinely froze the mechanism shut.

Left: “U.S/S. NORTH/MIDLtn/CONN./1831”; the “crown over V” stamp is an English viewer’s mark. It was struck into the block before the block received its final grayish color case hardened finish. This suggests that an English gun manufacturer, unidentified, viewed and marked this gun at North’s Middletown, CT, factory in order to comply with English inspection laws to take home and perhaps evaluate prospects for commercial or military sales in England. The barrel also bears this viewer’s stamp. Above: “J. H. HALL/H. FERRY/US/1838”

“being a breechloader, has a merit few arms of its adaptability of being loaded by the soldier–on the ground, beneath log, or behind a tree or other protection without exposure of person to the mark of a rifleman.” The U.S. Model 1817 “Common Rifle,” a muzzle loader (but with a rifled bore for long range accuracy far superior to that of a smooth-bore musket), was produced under War Department contract in this period with four private arms manufacturers (three in Middletown, CT) for distribution to state militias under provisions of the 1808 Militia Act. The Act also stipulated that National Armory-made weapons (Harpers Ferry and Springfield) were “reserved solely for the use of U. States troops.” Several defense-minded states clamored for this latest and greatest breechloader, leading to an 1828 War Department sole-source contract with North for 5,000 Hall pattern rifles at $17.50 each, most of which did go in small lots to various militias. North was an easy choice. He had made the second greatest number of private contract firearms for the War Department to that time: 50,000 flintlock pistols in seven different year/model designations and most recently 7,200 of the flintlock Model 1817 “Common Rifles.” Whitney, of New Haven, Connecticut, was a close first with 67,000 muskets. The last batch of Hall-North contract rifles was delivered in 1836. North subsequently received federal contracts for 16,000 shorter carbine versions of the Hall, with new percussion ignition and improved gas seal features, in the early 1840s. The initial infatuation with the Halls dimmed in the 1830s as harsh reports came in from the field listing such serious short comings as stock breakage and alarming breech gas leaks upon firing, and burnt power build-up that locked the breech block closed. Ordnance Department Lt. Colonel George Talcott observed dispassionately, “But fashions change and what is good today will be cried down to-morrow.” The Secretary of War was more direct and blunt in 1840: “I would not have adopted them and shall make little use of them hereafter in the regular service.” Muzzle-loading rifles of U.S. model years 1841 (made by Harpers Ferry and several private contractors) and 1855 (Harpers Ferry, exclusively), quickly supplanted the Hall Rifle. Federal arsenals reported in October of 1860 that in excess of 16,000 Hall rifles, flint and percussion, were in storage, most destined to be sold soon at obsolete ordnance public auctions.

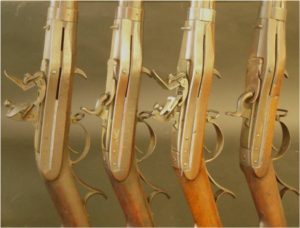

Left to Right:

“J. H. HALL/H. FERRY/US/1838”; Accession # 2017.202; purchase)

“J. H. HALL/H. FERRY/US/1831”; (Tag # 33; Gift, Pratt-Whitney Foundation, 1957)

“U.S/S. NORTH/MIDLtn/CONN./1831”; (Accession # 2017.369; purchase)

“U.S/S. NORTH/MIDLtn/CONN./1835”; (Accession #2017.193; purchase)

Hall Rifles: Flintlock and Percussion Ignition Conversions, Paired

The year of production date is stamped on the breech block. Most of the Hall pattern rifles stored in U.S. arsenals in the 1850s were converted to the newer, more reliable percussion ignition system. Flintlock hammers (also termed “cocks”), sparking steel frizzens (“batteries” and, confusingly, “hammers”) and pans were removed and striking hammers and percussion cap cones were installed. Note the long, narrow slots to vent hot gases exploding out of the breech with each shot. These slots are on the opposite side, as well.

The spur catch (right) locked shut and released the breech block within the receiver. The block pivoted on a heavy screw set through the hole behind the hammer. The screw-adjustable trigger (left), which tripped the hammer, could be set to suit the marksman. The frizzen “V” spring and three other lock flat springs required only a screw driver for cleaning removal. Resourceful soldiers sometimes set the mechanism into an improvised wood handle as an off-duty, make-do handgun.