By David Corrigan

Originally published in Connecticut Explored 2012

In 1808, former President John Adams trenchantly observed, “The state of Connecticut has always been governed by an aristocracy, more decisively than the empire of Great Britain is. Half a dozen, or, at most, a dozen families, have controlled that country when a colony, as well as since it has been a state.” In 1817, a writer using the pen name of “Michael Servetus” observed in the Times newspaper on October 11, 1817, “…although according to the constitution the officers of the government are chosen annually, yet from practice it has become a principle that every man who is once placed into an office, is permitted to die out of it, and that this is what in Connecticut is meant by rotation in office…”

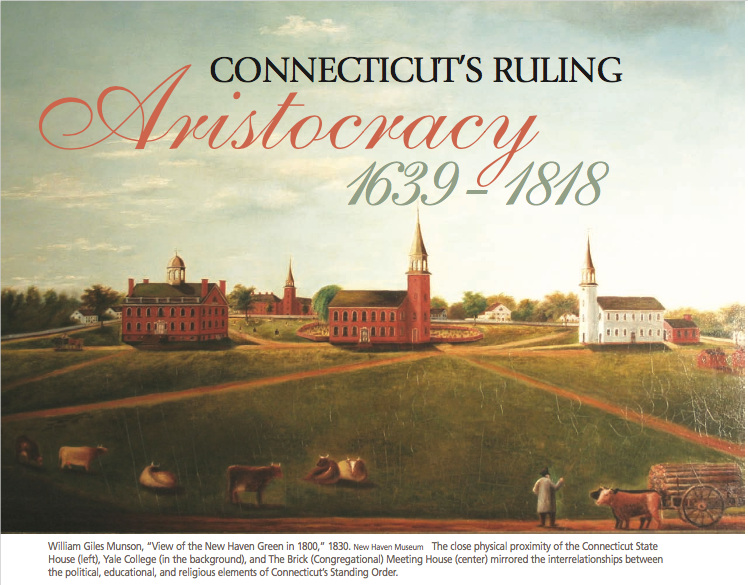

From 1639, with the adoption of the Fundamental Orders, to 1818, when the state’s first constitution was ratified, “…almost every aspect of life in Connecticut…(was) controlled by the Standing Order (which) consisted of an elite group of intellectuals, politicians and religious leaders,” writes George Curley in his 2007 master’s thesis “The Fall of the Standing Order: Connecticut 1800-1818.” Congregationalism was the established religion, politicians were uniformly members of the Congregational Church, and Yale College, established and overseen by the Congregational Church, produced the intellectuals and ministers that provided justification for the continuance of traditional Connecticut politics.

Longevity in office was one of Connecticut’s steadiest habits for nearly 150 years, grounded in an apprentice system in which suitable candidates were identified at the local level and were nurtured and tested in elections for offices of increasing importance and responsibility. This weeding-out process produced candidates ultimately deemed worthy of election to the highest offices in the state: governor, deputy governor, secretary of the state, and treasurer. This system, combined with a traditional fear of political upheaval, suffrage based on property ownership that … “disenfranchised a substantial number of… residents,” and the custom of placing incumbents’ names at the top of the ballot above those of lesser-experienced rivals, resulted in the near-constant re-election of incumbents and a uniquely Connecticut brand of political stability, notes Andrew Siegel in “‘Steady Habits’ Under Siege: The Defense of Federalism in Jeffersonian Connecticut” (in Federalists Reconsidered, University Press of Virginia, 1998). It also created a situation in which a candidate for any high office likely belonged to one of a small number of long-established Connecticut families.

In 1801, “The Lover of Old Steady Habits,” writing in the Connecticut Courant, described the weeding-out process as producing candidates “…who had been tried, and proved, [moving upward]from post to post, until they had arrived at the highest honors in the government:—men who sustained fair characters, whose lives were free from vices, who were attached to the established systems of the State, who revered, and cherished its civil, moral, and religious institutions.” As proof that the system worked, the writer urged his readers to “Witness the venerable names of SALTONSTALL, FITCH, LAW, PITKIN, TALCOTT, TRUMBULL, GRISWOLD, HUNTINGTON AND WOLCOTT….whose names will be respected, and whose memories will be cherished, as long as true merit is loved, and patriotism regarded in the state….” These were nine of Connecticut’s most revered and ancient families.The career of Matthew Griswold (1714-1799) of Lyme serves as a typical example of that apprentice system. Griswold was in the fourth generation of one of the wealthiest and most respected families in Connecticut. He was made captain of the local Train Band, or militia, in 1739, when he was 24. He opened a law practice in 1742 and was named king’s attorney for New London County the following year, serving until 1776. First elected to the colony’s general assembly in 1748 at age 34 for one year, he later served from 1751 to 1759. For the next 10 years he served on the council of assistants, serving simultaneously as a judge of the superior court from 1765 to 1769. In 1769, at age 55, he was elected deputy governor and, by law, also served as the chief justice of the superior court straight through from the colony’s transition to the State of Connecticut until 1784, in which year, at age 70, he was elected governor, serving two one-year terms.

Unlike Adams and “Michael Servetus,” Timothy Dwight saw virtue in the system. Dwight, the staunchest defender of the Standing Order and “steady habits” in politics, noted in his Travels in New-England and New-York (self-published by Timothy Dwight, New Haven, 1821), “Connecticut is a singular phenomenon in the political sphere. Such a degree of freedom was never before united with such a degree of stability,…” the first cause of that stability being “our [English] ancestors.” Furthermore, the circumstances under which Connecticut was founded and continued “operated so powerfully as to give entire consistence to the political structure originally erected.” As a result, Dwight approvingly noted that “The great officers of this state are few, …their continuance in office is usually long,” and “the incumbents, except those who belong to the House of Representatives, hold [their offices]with a stability unparalleled under any monarchy in Europe.”

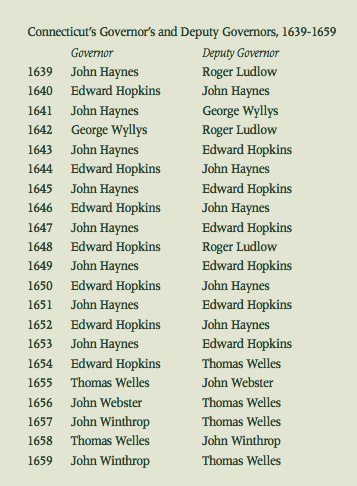

The political stability Dwight lauded had been established in the earliest days of the colony, despite the provision in the Fundamental Orders prohibiting a governor from succeeding himself in office. For the first 20 years of the colony’s existence, the office of governor was held by seven men, with two of them, John Haynes and Edward Hopkins, alternating as governor and deputy governor for 10 of those years. These first seven leaders of the colony rotated in the two highest offices, succeeding each other, since they were prohibited from succeeding themselves. Thomas Welles has the added distinction of being the only man in Connecticut history to have occupied all four of the highest offices: treasurer (1639), secretary of the state (1640-1649), deputy governor (1644, 1646, 1647, and 1649) and governor (1655, 1658).

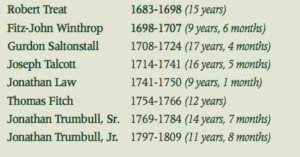

In 1660, the law was changed to allow governors to serve successive one-year terms, and the practice of returning incumbents to office began in earnest. John Winthrop was re-elected and served 16 consecutive terms until 1676, for a total of 18 years in office. In the 141 years from 1676 to 1817, 17 men served as governor, each averaging a little more than 8 years in office. However, of these 17 men, 8 served for a total of 105 years, 7 months, averaging slightly more than 13 years in office each:

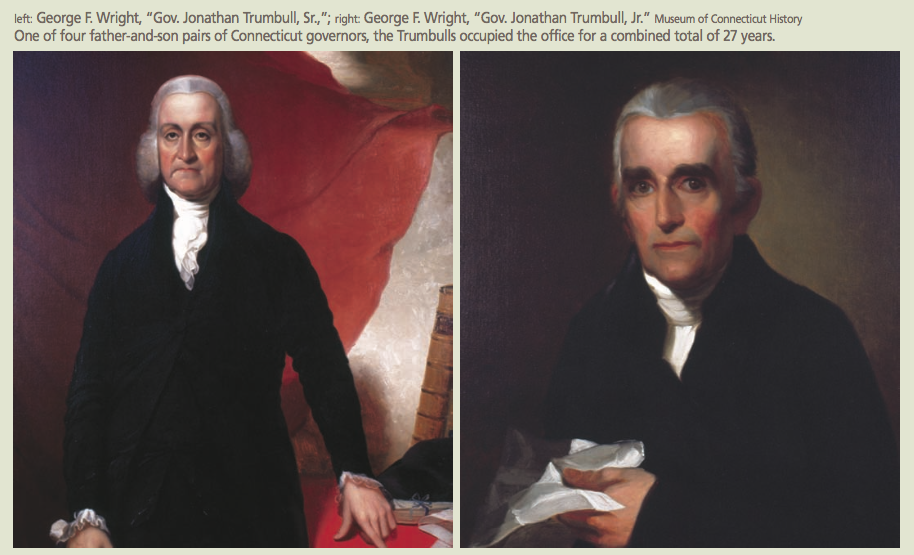

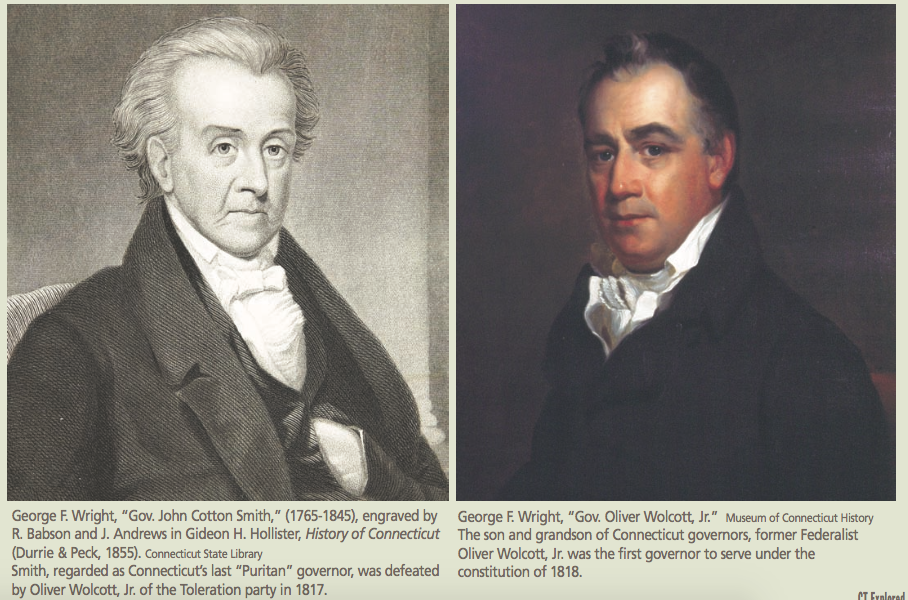

The table hints at another aspect of politics in colonial and Federal Connecticut—that of the multiple generations of families who occupied the office of governor. Connecticut has had three families in which both father and son held that office (Winthrop, Trumbull, and Griswold) and one family (Wolcott) in which three generations did so. Fitz-John Winthrop was the son of John Winthrop. Jonathan Trumbull, Sr. and Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. together occupied the office for more than 25 years. Matthew Griswold served from 1784 to 1786, and his son, Roger Griswold, was elected in 1811, re-elected in 1812, and died while in office. Roger Wolcott served from 1750 to 1754; his son Oliver Wolcott, Sr. served from 1796 to 1797, and his grandson, Oliver Wolcott, Jr., served from 1817 to 1827. Of these seven men, only Fitz-John Winthrop and Oliver Wolcott, Jr. had not served as deputy governor prior to assuming the governor’s office.

In addition to the gubernatorial grandfather, father, and son lineages, there was a wider family dynamic at work between the Wolcott and Griswold families. Both had achieved prominence over many years and, like most early Connecticut families, had intermarried. In November 1743, Matthew Griswold married his second cousin, Ursula Wolcott; their marriage, according to Glenn E. Griswold, a family genealogist, “…reunited two of [Connecticut’s] leading families by a new tie of blood.” Ursula Wolcott Griswold became the daughter, wife, sister, and aunt of a Connecticut governor. She was the daughter of Roger Wolcott, who, at the time of her marriage, was serving as deputy governor and would later serve as governor. Her husband Matthew Griswold served as both deputy governor and governor. Matthew and Ursula Griswold’s son, Roger (probably named after his maternal grandfather) was also deputy governor and governor. Ursula Griswold’s brother Oliver Wolcott, Sr. served as deputy governor and as governor, and his son Oliver Wolcott, Jr. (more about him, one of the new breed of politicians, below), Ursula’s nephew, served as governor from 1817 to 1827; he was the first governor to serve under the Constitution of 1818.

A preference for incumbency and family dynasties also characterized the office of secretary of the colony and, later, the state.. The first secretary of the colony was Edward Hopkins, who served from 1639 to 1641, apparently serving simultaneously as secretary while governor in 1640. He was succeeded by Thomas Welles, who served for 7 years (1641 to 1648), followed by John Cullick of Hartford, who served for 10 years (1648 to 1658). From 1658 to 1709, three men—Daniel Clark of Windsor, John Allyn of Hartford, and Eleazer Kimberly of Glastonbury—occupied the position, with Allyn serving for 30 years, from 1664 to 1665 and from 1667 to 1696.

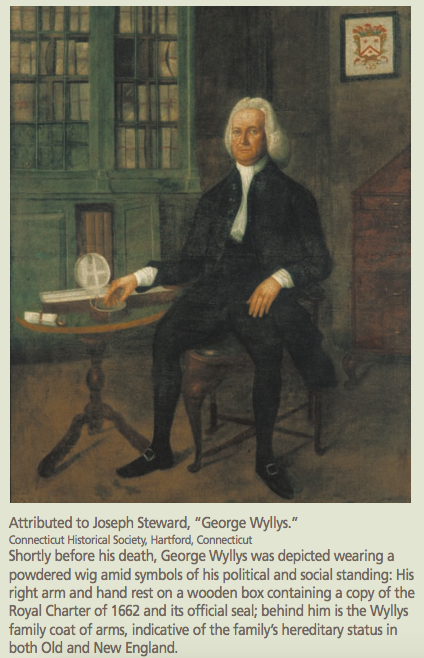

But none of those families could match the Wyllys family, which took possession of the position of secretary of the colony and, later, the state, and kept it for an unprecedented 98 years. From 1712 to 1810, three generations of one of Hartford’s most prestigious families successively occupied the position: Hezekiah Wyllys from 1712 to 1735; his son George from 1735 to 1796 (61 years!); and his grandson Samuel from 1796-1810. The Wyllys dynasty was succeeded by Thomas Day, who served for 25 years (1810 to 1835). For nearly the first 200 years of its history, Connecticut had only 13 secretaries of the state..

The office of treasurer had a similar pattern. The second secretary of the colony, Thomas Welles served as treasurer for two years before becoming secretary in 1641. He was succeeded by William Whiting (who served from 1642 to1648) but then succeeded him and served again as treasurer from 1648 to 1652. (Welles then served consecutively as either governor or deputy governor from 1654 to 1659.) John Talcott, Sr. and John Talcott, Jr. held the treasurer position after Welles, from 1652 to 1676. Treasurer William Whiting’s son Joseph then served for 39 years, from 1679 to 1718, and his son John served nearly as long, from 1718 to 1750. From 1756 to 1818, five men occupied the position of treasurer, three of them serving terms of 13, 20, and 24 years. Three generations of Whitings held the position for 78 years, while three generations of Talcotts held it for 37 years.

Although Timothy Dwight and “The Lover of Steady Habits” endorsed the long-standing traditions of incumbency and a ruling elite, not everyone surveying Connecticut politics was as enthusiastic about the practices, and many were becoming disenchanted. After nearly 150 years, Connecticut’s Standing Order—the nexus of political, clerical, and social power—came under increased attack, beginning in the 1790s. Defenders of the system, most of them descendants of the state’s first families, had become Federalists and vigorously opposed efforts of the Republicans, citizens of a Jeffersonian persuasion, to effect change. The Republicans espoused a broadening of the electoral franchise, the severing of the tax-supported link between the state and the Congregational church and, ultimately, the drafting and ratification of a new state constitution to replace the Royal Charter of 1662.

Early Connecticut Republicans were influenced by both the first, democratic aspect of the French Revolution and by positions espoused by Thomas Jefferson. Some were former Federalists and Congregationalists, but many were Episcopalians, angered at the Congregationalists’ refusal to allow them equal status, Baptists, and, later, Unitarians and Universalists. All were more liberal and tolerant than members of the Standing Order.

The Republicans first ran candidates for office in 1796 and established a statewide organization in 1800. In the elections of that year, Republicans received nearly one-third of the votes and ran candidates in every election after that. Efforts to break the hegemony of the tradition-bound Federalists finally bore fruit in the elections of 1817 and 1818. Oliver Wolcott, Jr. was elected governor in both years, and in 1818 the Toleration Party, formed in 1816 as a coalition of Republicans, religious dissenters, and other residents seeking broad political change, captured both houses of the general assembly.

Oliver Wolcott, Jr., although a scion of one of the old families, was not a product of the traditional political system. His moderate political views, his name, and his social standing combined to make him appealing to a broad spectrum of reform-minded Connecticut voters.

By Connecticut political standards of the early 1800s, Oliver Wolcott, Jr. was the black sheep of the Griswold-Wolcott family. He was born into the Standing Order, graduated Yale College in 1780, and, in 1785, married Elizabeth Stoughton, step-daughter of Samuel Wyllys, secretary of the state from 1796 to 1810. But he was not a product of Connecticut’s political apprentice system, and his only previous state service was from 1788 to 1790 as comptroller, a position created in 1786. He spent most of his public life in federal service and was later in business in New York. He became a moderate Federalist and supported the War of 1812. In 1813 he and a brother erected a woolen mill in what became the Wolcottville section of Torrington. He retired to Litchfield in 1815 to assist in running the mill. Franklin B. Dexter noted that, by 1816, his “name was widely acceptable, especially to those supporters of the (Republican/Toleration) ticket who had formerly voted with the Federalists and to those who desired protection for manufactures.” (“Oliver Wolcott,” in Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College. Vol. IV, New York, Henry Holt, 1907.)

Wolcott defeated John Cotton Smith, who represented the old Standing Order, in the gubernatorial election of 1817. A veteran of state politics, Smith was descended from several New England ministers; his father was Cotton Mather Smith. The younger Smith served as lieutenant governor from 1811 to1812 and became the last Federalist to serve as governor, doing so from 1812 to 1817. Gideon H. Hollister, in his 1855 History of Connecticut (Durrie & Peck, New Haven), noted that “…with the fall of his party (he) retired from the political arena….[unable]to adapt…to the new order of things,” with Wolcott becoming “…a very important pillar of the edifice that was to be built upon the ruins of the old one.”

Hollister also provided a fitting summary of Connecticut’s transition to modern politics:

As Governor Smith’s administration was the last which represented the commonwealth, in the days of Haynes, Wyllys, Winthrop, Treat, and Saltonstall, so on the other hand, Governor Wolcott’s was the first that embodied the principles of republicanism or democracy, as all political parties now understand the term…. The former…upheld a particular ecclesiastical system,…and sustained a high-toned aristocratical sentiment with distinctions in society marked sometimes by the hereditary influence of half a dozen generations; the latter,…declared that the church and state should have no political affinities,…and that no social distinctions should be tolerated by the constitution, or countenanced by the state.

Hollister was born in 1817, the year Connecticut Federalism lost its hegemony over the state’s political apparatus, and his comments on governors Smith and Wolcott, published nearly 40 years after their tenure, evince a sense of loss for an era that he had never experienced, yet knew of and somehow lamented. But by 1817 Connecticut’s aristocratic political system was gone forever and a new, more modern system was emerging. Longevity in office was still possible—witness Governor John Dempsey’s term (1961-1971) and Governor William O’Neill’s (1980-1991)—but in the 20th century the phenomenon had more to do with demographics, modern political party structure, and the fact that the governor’s term of office was extended to four years in 1950, although term limits for the governor, abolished in 1660, have never been re-imposed.