David Corrigan:

Curator of the Museum of Connecticut History.

First produced for the Connecticut Explored magazine

By the mid-1890’s the bicycle craze in America was beginning to wane and Colonel Albert Pope, who had induced the fad, was actively seeking ways to diversify and maintain his manufacturing empire.

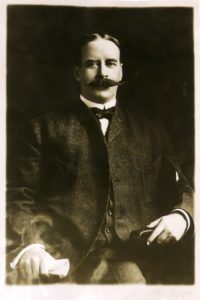

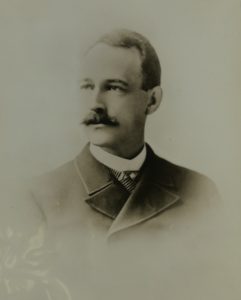

Horseless carriages were beginning to be developed in the United States, and Pope and his general manager Geroge H. Day were determined to enter the fledgling business. To that end, in 1895 Pope hired Hiram Percy Maxim (1869-1936) as an engineer to develop the Pope Manufacturing Company’s Columbia Motor-carriage. Both Pope and Day firmly believed that electricity was far superior to gasoline as a motive force for a horseless carriage, since an electric vehicle as quieter, smoother running, less greasy and far safer.

When Day encountered the first gasoline powered vehicle Maxim developed for Pope, Maxim reported that Day “acted as though he were standing beside a tone of naked dynamite. I think he expected the contraption might burst at any time and rend him.”Maxim had come to the attention of Pope and Day as a result of his successful grafting of a small gasoline engine onto a second-hand Pope manufactured Columbia tandem tricycle in 1894. In the spring of 1895 Maxim traveled from Lynn, Massachusetts, where he was employed by the American Projectile Company, to Hartford to tour several of the more prominent factories Pratt & Whitney, Pope Manufacturing, and Hartford Rubber Works among others.

While at Pope he was reunited with Lieutenant Hayden Eames, who had been the inspector for naval armaments made by the American Projectile, and had recently taken the job as manager of the Pope Tube Works, overseeing the manufacture of the steel tubing used in Pope Bicycles. Maxim, son of Hiram Stevens Maxim inventor of the first automatic machine gun, was born in Brooklyn New York and graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1886. He had worked as a draftsman at electric Companies in Massachusetts and Indiana and had been employed by the Thompson Electric Welding Company in Lynn before moving to American Projectile.

Despite his background and experience in the electrical field, Maxim did not share Pope and Day’s high opinion of an electric-powered vehicle, and accepted the position at Pope Manufacturing with the understanding that he would be able to work on both gas and electric designs. This was acceptable to Pope since, at this early stage of horseless carriage experimentation, there was no way to tell whether gas or electric-powered vehicles would garner the largest share of the market.

Given Pope’s preference, Maxim devoted his energies to designing and building an electric-powered vehicle known as “Mark I” Maxim noted that “In this new carriage nothing old need be used. The slate was clean. Everything would be designed for its purpose.” With a plan approved by Eames, Maxim set to work to make the Mark I a reality. He was immediately confronted with a basic problem. “I had to know the weight of the vehicle in order to select the storage battery that would be necessary to drive it. But eh weight of the vehicle could not be arrived at until I knew the weight of the storage battery.”2 Many trips to the Electric Storage Battery Company in Philadelphia and many conversations with the firm’s officers and chief engineer resulted in the selection of a size and type of lead storage battery that would reduce the Mark I’s mileage and speed, but which could easily be fitted to a carriage body.

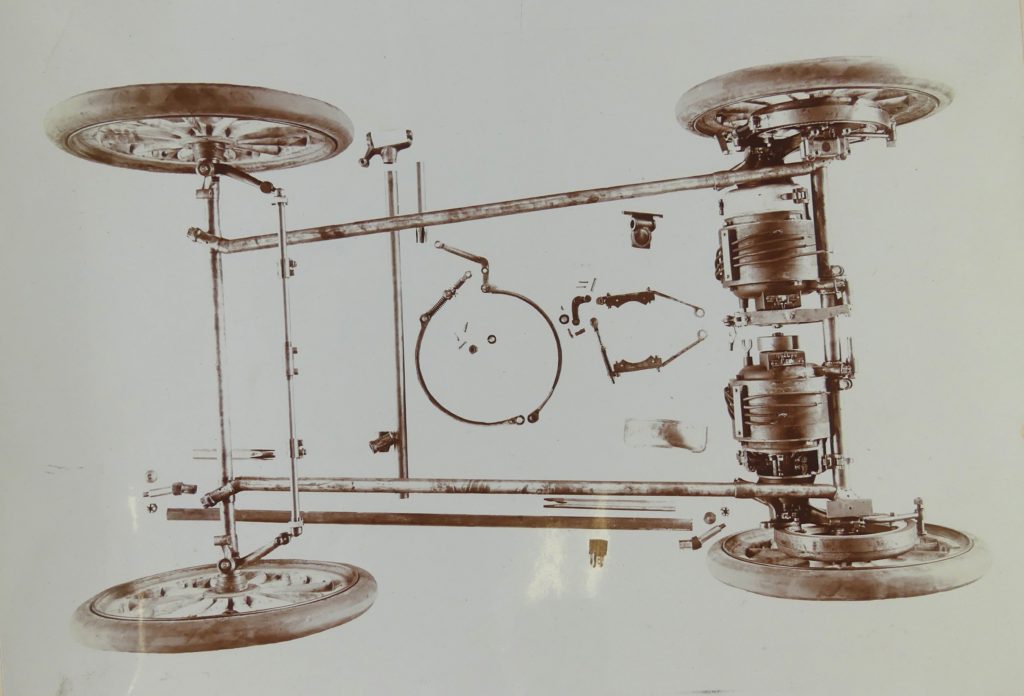

The electric motor also presented problems. Maxim needed to know its weight and speed as well as its torque characteristics. Fortunately, the Eddy Electric and Manufacturing Company in nearby Windsor was able to provide a motor that met all of Maxim’s weight, speed, and traction requirements. The Eddy motor was light and could run at 2,000 revolutions per minute. Maxim calculated that the top speed the Mark I needed was 12 miles per hour on a level road and designed a gear reduction system that translated the engine’s much higher speed into usable speeds for the carriage.

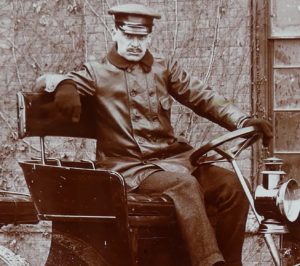

With the technical details worked out, Maxim turned his attention to the physical appearance of the Mark I. A basic design stipulation, accepted by all those working in the field, was that any finished horseless carriage must still look like a typical horse-drawn carriage. “The horse carriage was the standard and anything different was frowned upon. Maxim adopted the policy “to see that the boss, who was paying for it, got exactly the style and size of body he wanted. Pope and the officers of Pope Manufacturing selected a carriage body known as a “phaeton” for the Mark I. It was built by the Mansuy Carriage Company, located on Elm Street in Hartford. Although it was deemed “the most beautiful thing of its kind that had been produced up to that time, Maxim was concerned that the Mark I could only travel approximately 25 miles on one battery charge, and that its use was strictly limited to city streets and parks, In any event, Maxim successfully demonstrated the Mark I phaeton to Eames, Day, and Pope “and Connecticut’s first motor-car set forth in the streets of Hartford” in April 1896.6

Maxim’s demonstrations resulted in discussions among the three men regarding large-scale manufacturing of the vehicle. They began to speculate as to how much it would cost to manufacture them, where they would be manufactured, how much they could be sold for, and how many could be sold hi a year. Their speculations took concrete form in the decision to redesign the body of the Mark I, manufacture and thoroughly test one, then proceed to manufacture a lot of ten. The new model would be known as the Mark in, the Mark n having been a gasoline powered vehicle. As a first step, Maxim and Day consulted with William Hooker Atwood, designer at the New Haven Carriage Company, and his draughtsman, Paul Steinbeck. Atwood was a strong traditionalist, attuned to any potential deviation from the long-standing design requirements of a “gentleman’s carriage.” Maxim’s suggestion to round a corner here and there was met by Atwood’s rebuke “Leave it sharp! That’s smart and elegant.” Maxim admitted that he “hungered for lots of shiny nickel plate. It suggested fire engines and interesting machinery” but that “Mr. Atwood sickened at the mere thought.

Another holdover from carriage design in the Mark in was the differing sizes of the front and rear wheels. Maxim suggested that, for efficiency and ease of changing tires, all four wheels be the same size, but Atwood refused to implement the modification on aesthetic grounds. Eames himself negotiated a change in the shape of the dashboard. Atwood argued for the traditional horse carriage design and Maxim strenuously objected, believing that it “took the horse carriage idea to an extreme. I was so completely out of harmony with it that I suggested adding a whip socket, which hurt Mr. Atwood’s feelings.” Eames’s compromise design, incorporated into the Mark HL became the industry standard and was known as the “Eames dash.”® Other small compromises were achieved and the final design of the carriage body was approved.

The experimental Mark III was road tested late in 1896. After several small details were corrected, the vehicle was ready to be put into production. A manufacturing department was created in the Motor Carriage Department, and A.F. Bardwell was hired as superintendent. Maxim had done all his experimenting on both gasoline and electric vehicles in a section of the Pope plant at the corner of Park and Laurel streets. This three-story, 50-feet-wide by 266-feet-long building was designed by George Keller. It had been erected in 1892 and was known as the “tube mill,” a designation derived from the fact that all the tubing used in the frames of Pope’s Columbia bicycles was made there, In the summer of 1896 Pope moved his tube manufacturing to a new building on Bartholomew Street, and the Hartford Board of Trade later reported that the original “tube mill” was “now used for the development and construction of the motor carriage.” Elaborating on the Pope project, the Board noted that “It is expected that the first lot driven by electricity will be completed the coming spring…. Abroad a great and growing demand for horseless vehicles has sprung up. It is believed that this establishment is about to furnish a model which will cause a like demand in America.

On May 13, 1897, Pope Manufacturing formally unveiled its Mark III phaeton in ceremonies held at the Laurel Street factory. Guests partook of refreshments in the front office, received a tour of the factory, and were then ushered out to the factory yard to see the ten production vehicles, three of which were made available for demonstration rides around the city. Maxim reported that he had little to do except mingle, be polite, and see that everything went well. Despite his success in having ten operational Mark III’s available for public scrutiny, Maxim was far from happy. “The knowledge that ten of my precious darlings were out on the road in the hands of ordinary human beings, who might not demonstrate them intelligently, nearly wore me down.

The Mark II unveiling was an unqualified success. The Hartford Courant article headlined “HORSELESS ERA COMES,” referred to the “wonderful new, thoroughly made, modern vehicles” as a “new departure in carriage locomotion.” The Mark III motor carriage ran on electricity stored in four sets of batteries that could be charged from any 110 volt circuit, the most common type of circuit then in use. “Anyone having electric light connection on his premises has his ‘horse’ at home, and can reinforce his supply of electricity as he pleases, enthused the Courant, underscoring the fact that the Mark III’s market, already limited to the more well-to-do, was even further restricted since, at the time, very few people, even in urban areas, had an electric light connection. The New York Times provided a more technical description of the Mark III, noting that the vehicle was equipped with a “two-horse power Eddy motor” powered by four battery units each weighing 200 pounds and that “the total weight of the carriage is about 1,900 pounds.” The Times also commented upon the Mark III’s “balance gear which enables the two rear wheels to revolve independently of each other while turning a curve.”12

Following the successful introduction of the Mark III, the Pope Manufacturing Company developed and manufactured a wide array of electric vehicles. These included an Opera Bus (used by fashionable people for transportation to and from the theater and the opera), an Omnibus, the Columbia Electric Victoria Mark V, the Columbia Electric Dos- a-Dos Mark VI, the Mark XI Electric Delivery Wagon, the Victoria Runabout, Mark XII, and the Mark XIX Surrey, all manufactured in the Motor Carriage Department at the corner of Park and Laurel streets.

While Pope wisely explored newly emerging electric-powered vehicle possibilities, the merger craze in American business exploded. Unfortunately Pope succumbed to the allure of a New York “combine,” which promised unlimited markets and financial gain. In April 1899 Pope and New York interests headed by William C. Whitney formed the Columbia Automobile Company, comprised of $3 million of Whitney’s capital and Pope’s Motor Carriage Department. One month later, the company name was changed to the Columbia and Electric Vehicle Company. As part of the agreement George, H. Day became head of the new company. Columbia and Electric Vehicle produced several hundred electric taxicabs that operated in New York City and several other major cities around the country. Maxim noted, however, “these cabs were doomed. The gasoline-engine [in the competition’s taxicabs] drove every one of them off the streets. Lighter weight, higher speed, lower first cost, and lower operating expense did the job.”5 Pope was bought out in June 1900, and the Columbia and Electric Vehicle Company was folded into the New York-based, Whitney-controlled Electric Vehicle Company. Pope’s eagerness to sell was fueled in part by his need to oversee the American Bicycle Company, a nation-wide federation of about 40 bicycle manufacturers, formed in 1900 in an effort to resuscitate and consolidate the slumping bicycle market.

In 1900 Hiram Percy Maxim joined the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in Pittsburgh shortly after the merger, but returned to Hartford in 1903 as the chief engineer for Electric Vehicle. The company, which manufactured both gasoline and electric vehicles, continued to manufacture motor carriages in Hartford for a few more years, but allegations of over-capitalization and stock-watering loomed large, and the public’s preference for gasoline-powered vehicles was becoming manifest.

In 1909, Maxim left the motor vehicle industry and founded the Maxim Silent Firearms Company to manufacture his patent silencer for firearms.

The last vestiges of Pope’s original Motor Carriage Department struggled into the 20th century. During these years the Electric Vehicle Company was embroiled in the famous Selden patent lawsuit against Henry Ford. Electric Vehicle went into receivership in 1907, emerging in 1909 as the Columbia Motor Car Company. In 1910, Columbia Motor Car was acquired by the United States Motor Company, which went into receivership in 1912. The physical plant of the original Motor Carriage Department was purchased and expanded by the Billings & Spencer Company in 1915 for its use. The factory was later demolished to make way for Interstate 84.

It has been said that Pope and Day put their money “on the wrong horseless carriage,” in opting for electricity over gasoline. Given the current resurgence of interest in electric and hybrid vehicles, the day may yet come when they outnumber the gasoline vehicles zipping along the interstate past the site where Pope and Maxim pioneered the electric motor carriage and wrote a major chapter in Hartford’s industrial history.